Electric Car Engineering: Electric cars, or electric vehicles (EVs), are revolutionizing the automotive industry. They offer a cleaner, more efficient alternative to traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, which burn gasoline or diesel to power their engines. But what goes into engineering an electric car? How do they work, and what makes them unique? This detailed explanation will explore the key components, systems, and technologies that define electric car engineering, breaking down complex concepts into accessible ideas. We’ll cover everything from the basics to the innovations shaping the future of transportation.

The Basics: What Makes an Electric Car Different?

At its core, an electric car operates on a simple principle: instead of burning fuel to power an engine, it uses electricity stored in a battery to drive an electric motor. This fundamental shift eliminates many of the complex mechanical parts found in ICE vehicles—such as pistons, crankshafts, and exhaust systems—while introducing new technologies that require precise engineering.

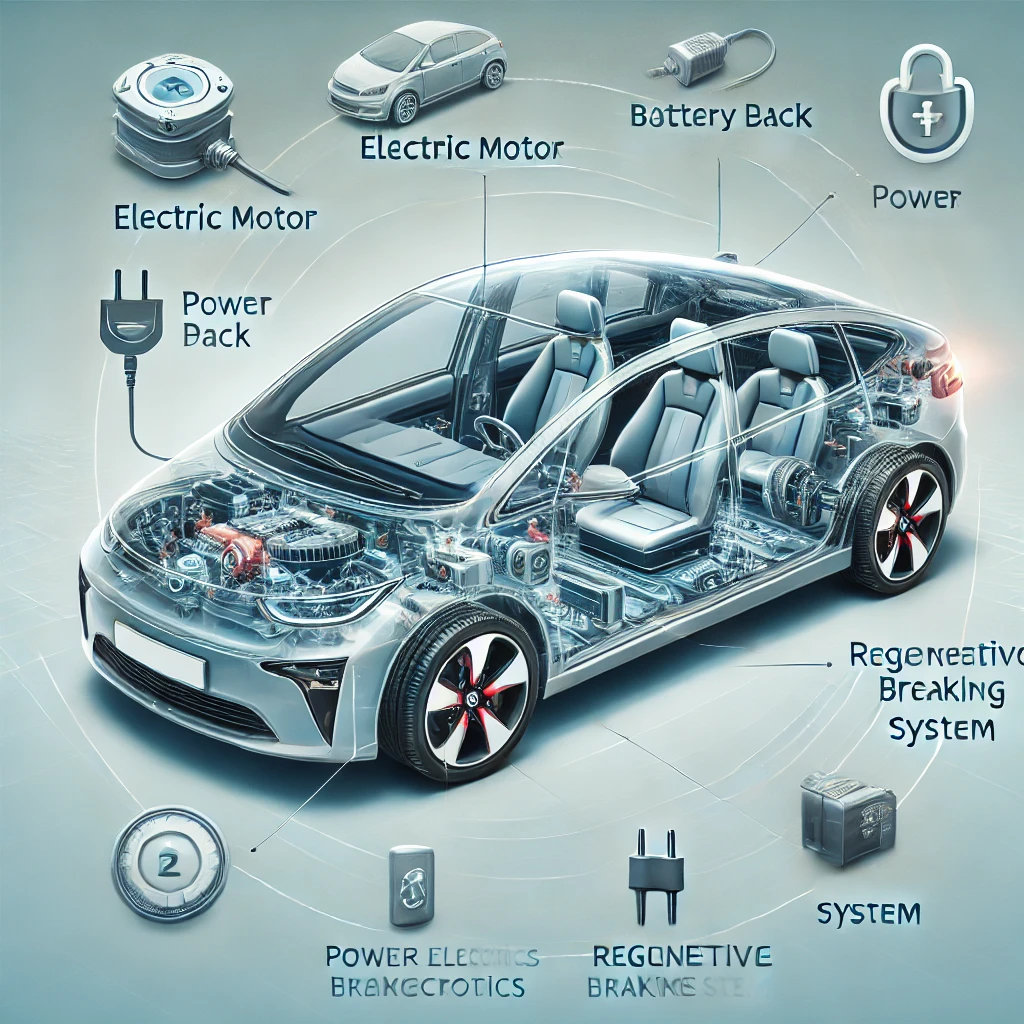

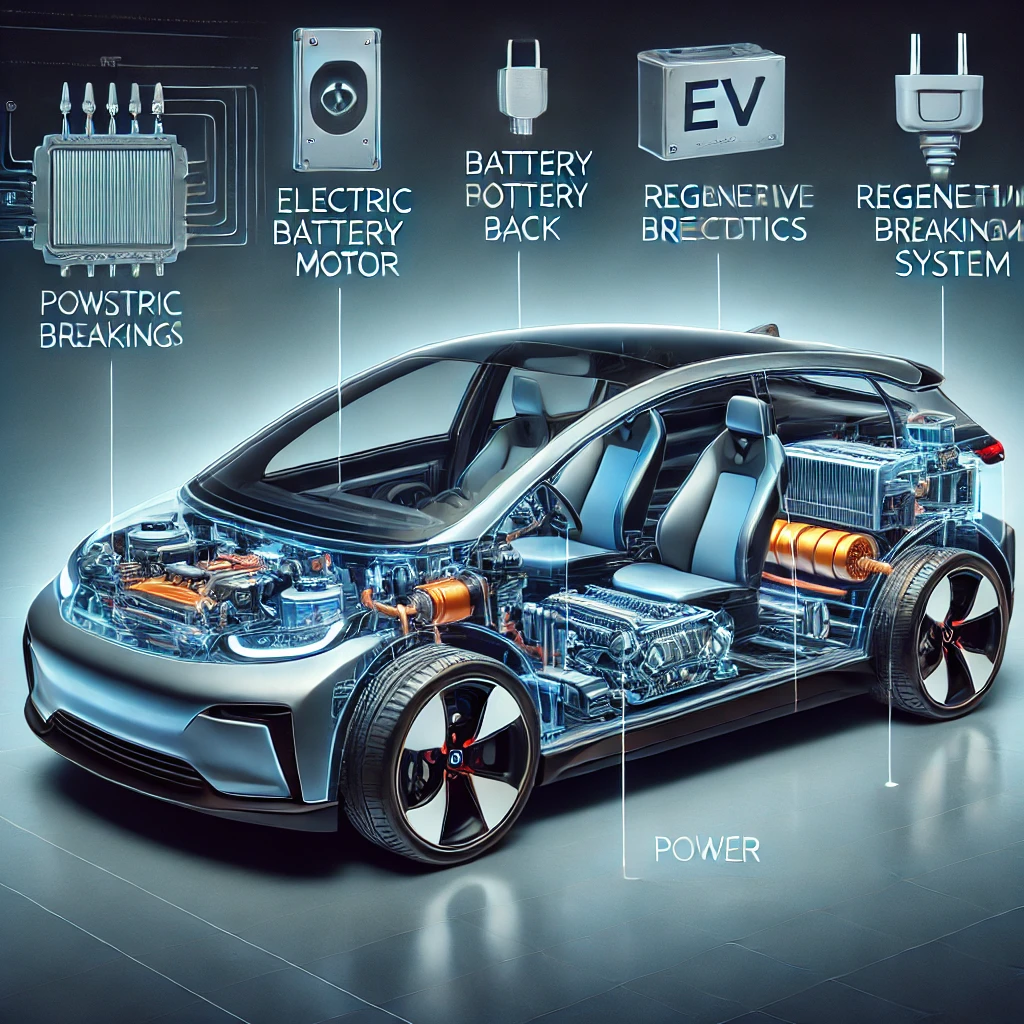

Key Components of an Electric Car

Battery Pack: The energy storage system, similar to the fuel tank in a gasoline car, but storing electricity instead of liquid fuel.

Electric Motor: Converts electrical energy into mechanical motion to drive the wheels.

Power Electronics: Manage the flow of electricity between the battery, motor, and other systems.

Charging System: Interfaces with external power sources to recharge the battery.

Thermal Management System: Keeps the battery, motor, and electronics at optimal temperatures to ensure performance and safety.

Chassis and Body: Designed to house these components while ensuring safety, efficiency, and performance.

Unlike ICE vehicles, which rely on a multi-speed transmission to manage power delivery, many EVs use a single-speed gearbox or direct drive. This is possible because electric motors deliver torque instantly across a wide range of speeds, simplifying the drivetrain. This simplicity is one reason EVs can be more reliable and require less maintenance than their gasoline counterparts.

The Battery Pack: The Heart of the EV

The battery pack is the most critical—and often the most expensive—component of an electric car. It stores the energy that powers the vehicle, and its design directly impacts range, performance, and cost.

Battery Chemistry and Cells

Most modern EVs use lithium-ion batteries due to their high energy density, long lifespan, and ability to recharge quickly. These batteries consist of thousands of individual cells, each containing:

Cathode (Positive Electrode): Typically made from materials like lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) or lithium iron phosphate (LFP). NMC offers higher energy density (more range), while LFP is safer and more durable but provides less range per kilogram.

Anode (Negative Electrode): Usually made from graphite, which stores lithium ions during charging.

Electrolyte: A lithium salt solution that allows ions to move between the cathode and anode during charge and discharge cycles.

When the battery discharges, lithium ions move from the anode to the cathode, releasing electrons that power the motor. During charging, the process reverses, with ions moving back to the anode.

Cell Formats

Battery cells come in different shapes, each with unique advantages:

Cylindrical Cells: Used by Tesla (e.g., 4680 cells), these are robust and easier to cool but less space-efficient.

Prismatic Cells: Rectangular and more compact, often used in EVs like the BMW i3.

Pouch Cells: Flexible and lightweight, common in vehicles like the Chevrolet Bolt.

Each format has trade-offs in terms of energy density, cooling efficiency, and manufacturing complexity.

Battery Pack Design

Cells are grouped into modules, which are then assembled into a battery pack. The pack is housed in a reinforced casing, often integrated into the vehicle’s floor to lower the center of gravity and improve handling. For example, Tesla’s “skateboard” design places the battery pack beneath the cabin, enhancing stability and safety.

Voltage and Capacity: Battery packs are wired in series and parallel to achieve the desired voltage (typically 400V or 800V) and capacity (measured in kilowatt-hours, kWh). A 100 kWh pack, for instance, can theoretically deliver 100 kilowatts for one hour. Real-world range depends on factors like vehicle weight, aerodynamics, and driving conditions.

Structural Integration: Some EVs, like the Rivian R1T, use the battery pack as a structural element, reducing weight and improving rigidity.

Battery Management System (BMS)

The BMS is the brain of the battery pack, monitoring voltage, current, and temperature for each cell or module. Its key functions include:

Preventing Overcharging/Overdischarging: Both can damage cells or cause safety hazards.

Balancing Cells: Ensures all cells charge and discharge evenly, maximizing lifespan.

Thermal Regulation: Activates cooling or heating systems to keep the battery within optimal temperature ranges (typically 20-40°C).

Without a robust BMS, the battery pack’s performance and safety would be compromised.

Electric Motors: Turning Power into Motion

Electric motors are the muscular system of an EV, converting electrical energy into mechanical motion. Unlike ICE engines, which have hundreds of moving parts, electric motors are remarkably simple, with just a few key components: a stator (stationary part) and a rotor (rotating part).

Types of Electric Motors

Most EVs use one of two types of AC motors:

Induction Motors: Popularized by Tesla, these motors use electromagnetic induction to create a rotating magnetic field. They’re durable and don’t require rare-earth magnets, but they’re less efficient at low speeds.

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM): Used by companies like BMW and Nissan, these motors incorporate permanent magnets in the rotor. They’re more efficient and compact, ideal for maximizing range, but rely on rare-earth materials like neodymium, which are costly and geopolitically sensitive.

Some EVs, like the Porsche Taycan, use a combination of both motor types to balance performance and efficiency.

Motor Placement and Configuration

Single Motor: Typically mounted on the front or rear axle, providing either front-wheel or rear-wheel drive.

Dual Motors: One motor per axle, enabling all-wheel drive (AWD) and better traction.

Quad Motors: One motor per wheel, as seen in high-performance EVs like the Rivian R1T. This setup allows for precise torque vectoring, where power is adjusted to each wheel for optimal handling.

The motor’s power output is measured in kilowatts (kW), with 1 kW equaling about 1.34 horsepower. A typical family EV might have 150-250 kW (201-335 hp), while performance models like the Tesla Model S Plaid exceed 760 kW (1,020 hp).

Torque and Efficiency

Electric motors deliver maximum torque from a standstill, providing instant acceleration. They’re also highly efficient, converting over 90% of electrical energy into motion (compared to 20-30% for ICE engines). This efficiency, combined with regenerative braking (which recovers energy during deceleration), makes EVs more energy-efficient overall.

Power Electronics: The Nervous System

Power electronics are the unsung heroes of electric car engineering, managing the flow of electricity between the battery, motor, and other systems. They ensure that the right amount of power is delivered at the right time, with minimal energy loss.

Key Components

Inverter: Converts the battery’s DC (direct current) into AC (alternating current) for the motor. It also controls the motor’s speed and torque by adjusting the frequency and amplitude of the AC output. Modern inverters use silicon carbide (SiC) transistors for higher efficiency and better heat tolerance.

DC-DC Converter: Steps down the high-voltage battery power (e.g., 400V) to 12V or 48V for auxiliary systems like lights, infotainment, and power steering.

Onboard Charger (OBC): Converts AC from a wall outlet or charging station into DC to charge the battery. The OBC’s power rating (e.g., 7 kW or 11 kW) determines how quickly the battery can be charged from an AC source.

Efficiency and Thermal Management

Power electronics handle massive currents—often hundreds of amps—while minimizing energy loss as heat. Efficiency is crucial: even a 1% improvement can significantly extend the vehicle’s range. To manage heat, power electronics are often liquid-cooled, especially in high-performance EVs.

Charging System: Refueling Reimagined

Charging an EV is fundamentally different from refueling a gasoline car. Instead of pumping liquid fuel, you’re transferring electrons from the grid to the battery. The charging system must be engineered to handle different power levels, voltages, and connector standards.

Charging Levels

Level 1 (120V AC): Uses a standard household outlet, delivering 1-2 kW. It’s slow, adding only 3-5 miles of range per hour, but useful for emergencies or overnight charging.

Level 2 (240V AC): Common for home and public charging, delivering 7-22 kW. It can add 20-60 miles of range per hour, making it ideal for daily use.

DC Fast Charging (400V-800V DC): High-voltage stations delivering 50-350 kW, capable of adding 100-300 miles in 20-30 minutes. Tesla’s Superchargers and the CCS (Combined Charging System) standard dominate this space.

How to Convert a Petrol Car to Electric: A Step-by-Step Guide

Charger-Battery Interaction

Fast charging requires careful engineering to avoid overheating or degrading the battery. Most EVs limit fast charging to 80% capacity, as the final 20% charges much slower to protect the cells. Some vehicles, like the Porsche Taycan, use an 800V architecture to enable faster charging without excessive heat buildup.

Wireless Charging

Emerging technology allows EVs to charge via inductive pads embedded in roads or parking spots. While still in development, wireless charging could eliminate the need for plugs, making EV ownership even more convenient.

Thermal Management: Keeping Cool Under Pressure

Batteries, motors, and power electronics generate significant heat, and extreme temperatures can degrade performance or cause safety issues. A robust thermal management system is essential to maintain optimal operating conditions.

Cooling Systems

Liquid Cooling: Most EVs use a liquid coolant (e.g., glycol) to circulate through the battery pack, motor, and power electronics. This is more efficient than air cooling and allows for precise temperature control.

Air Cooling: Some budget EVs, like the Nissan Leaf, use air cooling for the battery pack. While simpler and cheaper, it’s less effective in extreme climates.

Heating Systems

In cold weather, batteries lose efficiency and charging speed. To counter this, many EVs use:

Battery Preheaters: Warm the battery before charging or driving.

Heat Pumps: Recycle waste heat from the motor and electronics to warm the cabin, reducing the need for energy-intensive resistive heating.

Thermal management is a delicate balance: too hot, and components degrade; too cold, and performance suffers. Engineers must design systems that adapt to a wide range of environments.

Chassis and Aerodynamics: Building for Efficiency

Electric cars are heavy—battery packs can weigh over 1,000 pounds—so the chassis must be engineered for strength, safety, and weight distribution. Additionally, aerodynamics play a crucial role in maximizing range.

Chassis Design

Materials: Aluminum and high-strength steel are commonly used to keep the frame light yet crash-resistant. Some EVs, like the Tesla Model Y, use cast aluminum sections for added rigidity.

Battery Integration: Placing the battery pack low in the chassis lowers the center of gravity, improving handling and stability. This also frees up space for a “frunk” (front trunk) in some models.

Aerodynamics

A sleek design reduces drag, which is especially important at highway speeds where air resistance consumes significant energy. Key aerodynamic features include:

Low Drag Coefficient (Cd): The Tesla Model 3, for example, has a Cd of 0.23, one of the lowest among production cars.

Active Aerodynamics: Some EVs, like the Lucid Air, use adjustable vents or spoilers to optimize airflow based on speed.

Engineers must balance aesthetics, practicality, and efficiency when designing an EV’s body.

Regenerative Braking: Energy Recovery

One of the most innovative features of electric cars is regenerative braking. Instead of using friction to slow down (which wastes energy as heat), regenerative braking turns the motor into a generator, converting kinetic energy back into electrical energy to recharge the battery.

How It Works

When the driver lifts off the accelerator or applies the brake, the motor reverses its function, generating electricity that flows back to the battery. This not only extends range but also reduces wear on the physical brakes.

Adjustable Regen: Many EVs allow drivers to adjust the strength of regenerative braking, from mild (similar to engine braking in an ICE car) to aggressive (almost one-pedal driving).

Regenerative braking can recover up to 70% of the energy used during acceleration, making it a game-changer for efficiency, especially in stop-and-go traffic.

Software and Control Systems: The Brain of the EV

Modern EVs are as much software-driven as they are hardware-driven. Advanced control systems manage everything from battery health to motor performance, ensuring the vehicle operates efficiently and safely.

Key Software Functions

Energy Management: Optimizes power distribution between the motor, climate control, and auxiliaries to maximize range.

Torque Vectoring: Adjusts power to individual wheels for better traction and handling.

Over-the-Air (OTA) Updates: Allows manufacturers to improve performance, add features, or fix bugs remotely, much like a smartphone.

Autonomous Driving

Many EVs are equipped with advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), such as Tesla’s Autopilot or GM’s Super Cruise. These systems rely on sensors, cameras, and AI to enable features like lane-keeping, adaptive cruise control, and even limited self-driving.

Engineering Challenges and Innovations

Despite their advantages, electric cars face several engineering hurdles. Addressing these challenges is key to making EVs more accessible and practical for the masses.

Range Anxiety

Challenge: Limited range compared to ICE vehicles, especially in cold weather or when driving at high speeds.

Solution: Engineers are pushing for higher energy density in batteries, faster charging infrastructure, and more efficient powertrains. Solid-state batteries, which promise higher capacity and safety, are on the horizon.

Cost

Challenge: Batteries are expensive, accounting for 30-40% of an EV’s total cost.

Solution: Scaling production, improving manufacturing techniques (like Tesla’s “tabless” battery design), and exploring alternative chemistries (e.g., sodium-ion) aim to reduce costs.

Sustainability

Challenge: Mining lithium, cobalt, and nickel raises environmental and ethical concerns.

Solution: Recycling programs, second-life applications for used batteries, and research into less problematic materials are underway.

Cold Weather Performance

Challenge: Batteries lose efficiency in low temperatures, reducing range and charging speed.

Solution: Advanced thermal management, including heat pumps and battery preconditioning, helps mitigate these effects.

The Future of Electric Car Engineering

The EV revolution is just beginning, and several exciting innovations are poised to reshape the industry.

Solid-State Batteries

These batteries replace the liquid electrolyte with a solid material, offering higher energy density, faster charging, and improved safety. Companies like Toyota and QuantumScape aim to commercialize solid-state batteries by the late 2020s.

Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Technology

EVs could soon act as mobile energy storage units, feeding excess power back to the grid during peak demand. This would turn EVs into a valuable asset for grid stability and renewable energy integration.

Wireless Charging

Inductive charging pads embedded in roads or parking spots could allow EVs to charge without plugging in, making the process seamless and convenient.

Autonomous EVs

The convergence of EVs and self-driving technology could lead to fully autonomous electric taxis or shared mobility fleets, reducing the need for personal car ownership.

Conclusion

Electric car engineering is a multidisciplinary field that blends electrical, mechanical, and software engineering to create vehicles that are efficient, sustainable, and high-performing. From the battery pack to the electric motor, each component is meticulously designed to overcome unique challenges and push the boundaries of what’s possible. As technology advances and costs decrease, electric vehicles are set to become the dominant form of transportation, driving us toward a cleaner, greener future.

How Electric Motors Work (Explain That Stuff):

https://www.explainthatstuff.com/electricmotors.html